The previous blog about the ongoing project in Satara, “Economics and Psychology of Long Term Savings and Pensions” was an introduction to why time-preference inconsistency is important and how it may manifest itself. The current blog will attempt to describe how such a characteristic can be measured in a survey and how it should be interpreted.

The classic survey methods to measure time inconsistency (for example, see Ashraf, Karlan and Yin, 2006) involve hypothetical questions where a respondent is asked to choose between a sum of money immediately and a slightly larger sum after a period of time. The horizon for both these choices is short term. The response is then compared with the same question asked with a longer time horizon (Table 1).

Table 1

|

Option

|

Now

|

Now + 1 week

|

|

Option

|

After 1 year

|

After 1 year + 1 week

|

|

1

|

Rs.100

|

Rs.110

|

|

1

|

Rs.100

|

Rs.110

|

|

2

|

Rs.100

|

Rs.120

|

|

2

|

Rs.100

|

Rs.120

|

|

3

|

Rs.100

|

Rs.130

|

|

3

|

Rs.100

|

Rs.130

|

|

4

|

Rs.100

|

Rs.140

|

|

4

|

Rs.100

|

Rs.140

|

|

5

|

Rs.100

|

Rs.150

|

|

5

|

Rs.100

|

Rs.150

|

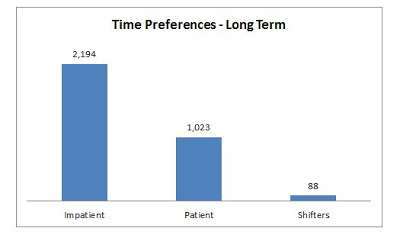

Asking this question for marginally increasing increments helps us figure out the rate at which respondents discount the future. Our baseline data indicates that out of 3305 respondents, 31 per cent are patient and two-thirds are impatient (Figure 1). Only three per cent of the sample shift (switch) their choices depending on the increment in the long run.

Figure 1

In the short run, however we find that 40 per cent are patient and 52 per cent are impatient; with seven per cent being shifters (Figure 2). We find that in the compared to the long term horizon, a larger share of the sample are patient, a lower share are impatient and the share of shifters/switchers more than doubles. The differences in the responses to both questions are statistically significant, that is, there are a significantly lower (higher) number of patient (impatient) people in the long term.

Figure 2

If a response to each choice set in the short term is not the same as that in the long term then he/she can be termed as “inconsistent” (roughly a quarter of our sample).

Figure 3

Hyperbolic discounters are those who are impatient in the short term and patient in the long term and reverse-hyperbolic discounters have just the opposite preferences. Consistent preferences indicate that there is no change in responses across the two time horizons. (See Figure 4 below)

Figure 4

Theoretically, our techniques are not able to capture “preferences”, which are of course abstract, but they are capable of capturing “revealed preferences”. The underlying rationale for these choices, hence, becomes very important. Whether impatience is a result of impending current needs or uncertainty about the future is entirely different from the impatience that arises from a lack of self-control (Ameriks et al,2007).These are some of the interesting questions which will help us understand our respondents’ long term saving behavior.