In the wake of COVID 19, Gig work emerged as a lucrative source of income generation for many. Significant advancements in technology, which allow quick access to and delivery of services even through mobile devices, have further enabled its proliferation globally. Additionally, increased inclinations towards part-time roles with flexible work hours as opposed to traditional roles also provide a significant boost to this industry. India accounts for 7.7 million gig workers, which make up 1.5 % of the workforce; it is estimated to grow to around 23.5 million by 2029-30

Despite the rapid growth of this work segment, the average monthly income of a gig worker in India is around INR 16000. Moreover, this form of work is accompanied by a lingering financial instability and uncertainty as well as limited financial and socio-welfare benefits and protections. Workers from marginalized socioeconomic backgrounds, who are dependent on day-to-day income are affected most in the absence of any financial safety nets to fall back on. Given this scenario, it is important to understand the financial health of gig workers. Additionally, measuring financial health is also paramount for creating financial health-centric policies and products that can improve financial well being. As part of the Community of Practice’s focus on financial health, LEAD at Krea University recently conducted a study with gig workers from seven states in India to better understand their financial behaviors and outcomes.

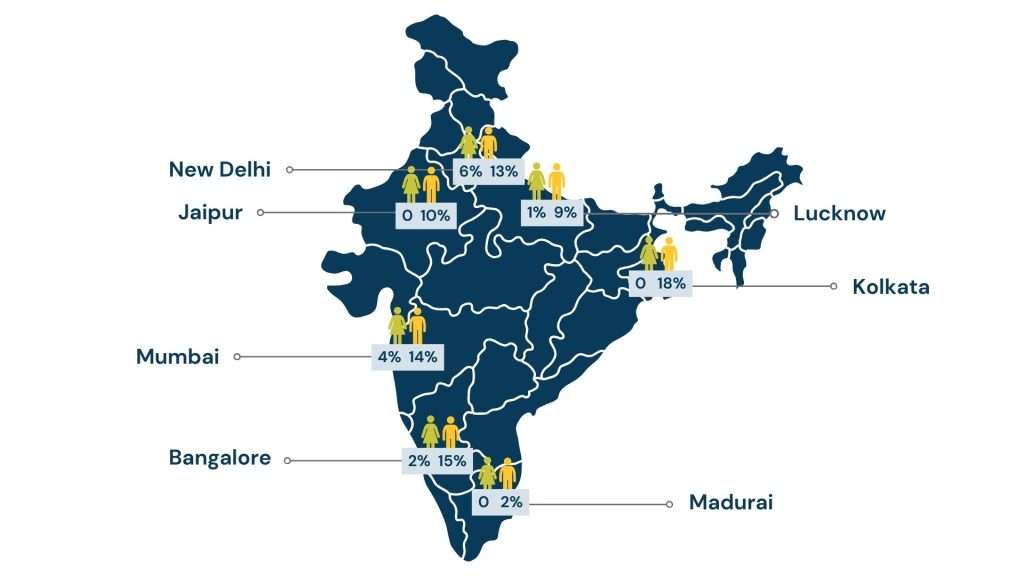

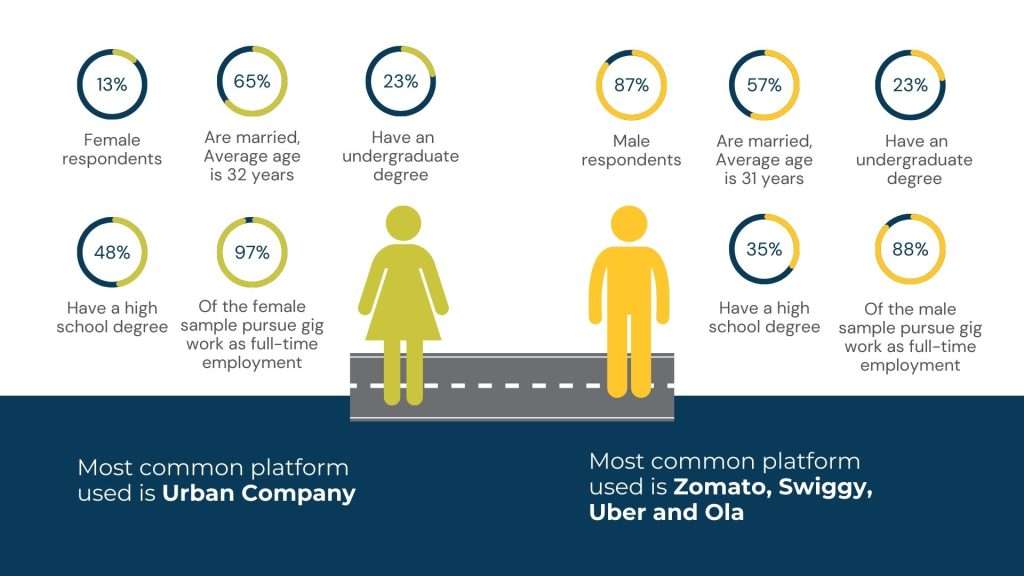

We conducted surveys with 521 gig workers; 87% male and 13% female workers associated with various digital platforms such as Uber, Ola, Urban Company, Zomato etc. The Global Findex 2021 report suggests that between 2011 to 2021, the gender gap in account ownership has decreased from 17 percentage points to nearly insignificant. Findings from our survey also suggest that 87% of female gig workers and 85% of male gig workers have bank accounts where they save their income. The remaining respondents also have a bank account but do not necessarily save there.

How do the platform workers earn, spend and save?

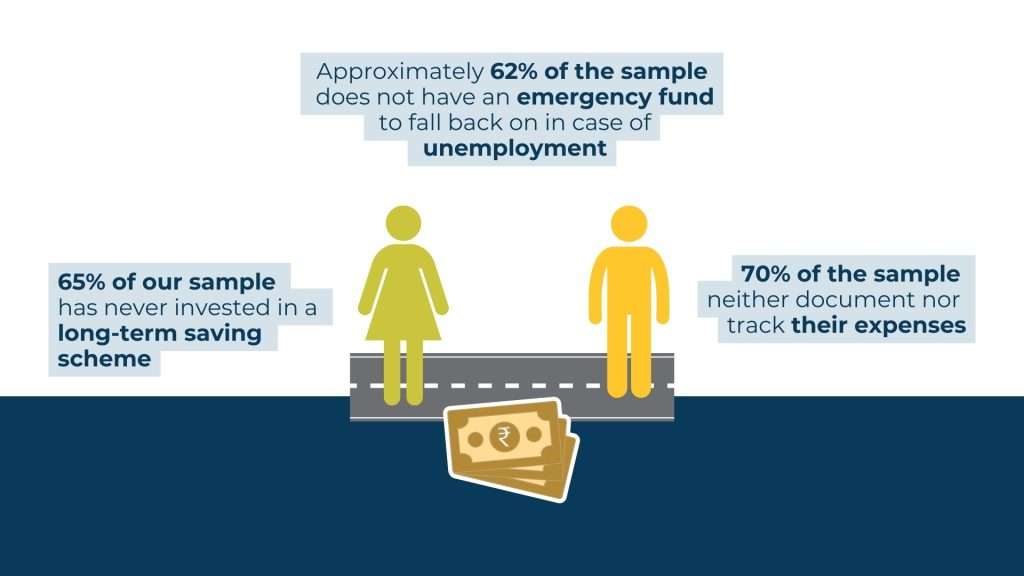

We find that only 45% of the workers were able to save every month; nearly 82% of these workers were saving less than half of their income. A major contributor to low savings being high cost of living expenses in the urban areas as 51% spend more than their income with more than 65% of their expenses resulting from essential expenses, leading to strained savings. While 54% of the workers could afford to save frequently on a monthly basis, 21% could only save annually. Out of those who could save; more than 70% saved in formal financial institutions and more than half preferred to save as cash at home. There was however a strong preference by women to save in formal financial institutions as compared to men. In a report released by CIIE.Co, 42% of the surveyed gig-workers reported not having an increase in their income over time and as a result nearly 51% reported not being able to save. This combined with the staggering fact that nearly 47% of these platform workers did not have any insurance, clearly highlighting the poor financial health of this growing population. As also suggested by a report by Dvara Research, most gig workers do not earn a minimum wage, are characterized by income volatility leading to uncertainty in income, high expenditure and resultant poor savings. Given the uncertainties and irregularities in income source, a gig worker often is not expected to maintain a regular frequency of savings.

Unlike a regular employed worker, gig workers have to often adopt flexible saving strategies with higher savings during peak income periods and a suggestive emergency fund to take care of uncertainties in lean income periods.

Income uncertainty is a major contributor to financial uncertainty among gig workers. We find that nearly 23% of the workers were unemployed at some point in the last one year. It was also interesting to note that nearly 21% of our respondents had joined the platform economy in the last one year. Moreover 59% of these workers get paid on a weekly basis and the remaining on daily basis, with a median income of INR 2,00,000 annually. The women participants in the survey who mostly engage with beauty and professional services earn income higher than the median income in our sample (INR 3,00,000 per annum); suggesting a wide variation in the income spectrum across platforms, nature of job and duration of employment. This calls for a closer look into the financial planning and resilience of the platform workers.

How resilient are the platform-workers?

Given the contractual nature of their jobs, gig workers are more prone to financial shocks, particularly during periods of unemployment. Financial well-being is defined as a person’s financial resilience (the ability to deal with an unexpected financial event), level of stress generated by common financial issues, and level of confidence in using financial resources in the global FINDEX 2021 report. We asked similar questions on resilience to understand if and how they could raise emergency funds in a situation of unexpected expenses. 62% of the gig workers did not have any emergency fund to fall back on under unexpected emergencies. However, 83.87% of the participants responded affirmatively to being able to raise a stipulated amount (INR 7500) within 30 days without much difficulty. They relied mostly on raising this amount from friends and family. Even though the gig work economy is mushrooming across the nation, gig workers in our sample are yet to be wholly absorbed into the formal financial system by way of developing sustainable financial behavior. This can be better achieved by raising awareness around the benefits of investing and by increasing access to many financial facilities which will enable them to plan their financial future even better. While efforts to save are being made, gig workers can be deemed financially healthy when their ability to fall back on financial safety nets by way of investments and borrowings from formal financial institutions increase.

Emerging issues and the way forward

The emerging findings discussed above suggest that there are multiple concerns like absence of assured income, infrequent savings as well as emergency funds, leading to a lack of reliance among the gig-workers. The lack of access to formal financial institutions for borrowings coupled with lack of efficient planning and long-term investments make this segment vulnerable to financial shocks and stress. With the boom in platform economy jobs and a change in the nature of work that comes with the sector, there is a need to better understand the financial lives of gig workers. Innovative product offerings such as flexible financial products (covering unexpected additional expenses or foregone income or lean/no income periods etc.) designed keeping in mind the nature of their work engagements and available resources (the traditional saving and insurance instruments) can provide a cushion from shocks. A life cycle approach of understanding an individual’s financial health and the need for appropriate products right from inculcating savings behavior leading to sound financial planning and investment that would have positive outcomes and ensure security in the retirement phase along with preparedness for “a rainy day” is the need of the hour.

This article was first published on Community for Financial Health’s Blog and is the second part of a two-part blog. Read the original piece here. The next part will bring forth insights from various dimensions of financial health from a survey with platform workers in India contributing to the development of the tool to measure financial health in low-income countries.

About the Authors

Sabina Yasmin is a Senior Research Fellow at LEAD and currently also serves as a Bharat Inclusion Fellow. Her research interests include agricultural economics, rural finance, development economics and applied microeconomics. Sabina is immensely passionate about using her work for the upliftment of marginalised people. Prior to joining LEAD, she taught economics to engineering and social science students at SRM University-Amravati.

Panchali Banerjee has a PhD. in Economics from Jadavpur University and a Master’s degree in Economics from University of Calcutta. Panchali enjoys researching corruption and social protection, and is particularly interested in intersections such as women’s work and gender-based violence.