Globally, 1.3 billion people (22 per cent) live in multidimensional poverty – with millions of households in 107 countries living with undernourished members, out-of-school children, and lacking access to electricity and clean cooking fuel. The Covid-19 pandemic is estimated to have pushed an additional 88-115 million people into extreme poverty in 2020 alone, primarily in countries that already have high poverty rates.

Moreover, social safety nets, an essential tool to help vulnerable populations cope with shocks and crises, remain out of their reach. With the Covid-19 pandemic, these vulnerabilities have been laid bare, especially in India – underscoring the need for a well-targeted, efficient and smoothly run social protection program. In this blog, we look at three private models engaged in social welfare delivery, combining human resources and social networks, with digital innovation.

Gaps in Welfare Delivery

India’s welfare delivery architecture has seen fundamental changes in recent years, accelerated by an active policy push towards direct benefit transfers (DBTs) and digitisation of delivery at central and local levels. However, challenges persist:

- Exclusion of citizens (especially at the last mile) – Digitisation of Direct Benefit Transfers (DBTs) have increased complexities in applying for welfare schemes. Such complexities are a result of myriad issues including limited access to banking infrastructure and access points such as Common Service Centres (CSCs), weak internet and electricity connectivity, lack of information about digital applications and online/telephonic grievance redressal processes, and inability to navigate the administrative architecture that overlays digitised application systems. Moreover, for new digital users, the tracking of application statuses and grievance redressal requests proportionately can be an intimidating and alienating process.

- Lack of administrative capacity and preparedness – The vision of leakage-free and technologically robust government-to-citizen (G2C) service delivery requires an efficient and competent body of local workers that can support the implementation of such a system. Such capacity gaps, at both the front-line and back-end, are giving rise to problems associated with back-end processing and database management of beneficiaries’ details – which further delays the time it takes for benefits to reach beneficiaries.

Rise of Platform-based Models

The need to transform the design and delivery of social security schemes has provided an impetus to innovative platforms and labour-saving solutions in India. While these platforms are a step further in digitising delivery processes, the ultimate future of platform-based digitisation remains to be seen – given organizational silos and fragmented efforts across different levels of governance.

In the wake of Covid-19 the pandemic, the Spanish National Health Service created Hispabot – a chatbot that answered basic health questions for citizens. The chatbot was integrated with WhatsApp, a communication platform extensively used by citizens. Hispabot increased access to healthcare for vulnerable populations and minimised pressure on the healthcare system.

Similarly, Mastercard has developed Community Pass, a digital platform that helps citizens access multiple services The platform facilitates service delivery, especially for marginalised individuals and communities through a Universal ID, including access to critical health services.

Private Initiatives in India

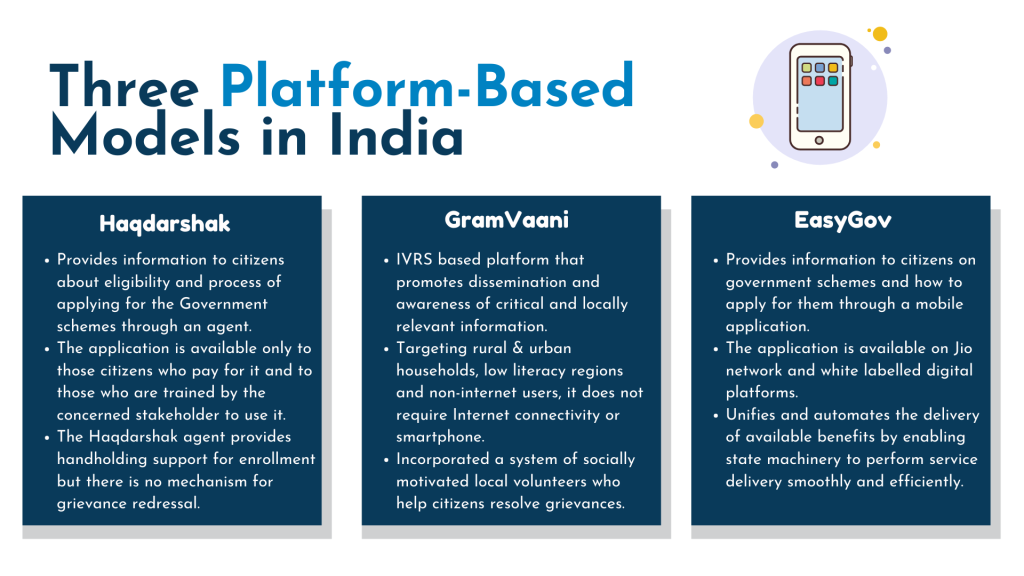

The three platform-based models discussed below and the core services they provide are reflective of three different but interlinked stages in the process of social welfare delivery – enrollment into welfare services, grievance redressal, and the back-end processing of applications.

The Haqdarshak Model

Haqdarshak Empowerment Solutions Private Limited (HESPL), a for-profit social impact organisation, has developed a mobile application and web platform called Haqdarshak, which contains ready information about application processes for more than 200 private and government entitlements operating at both national and local levels. The Haqdarshak platform collects and screens various aspects of citizens’ information (such as household details, income levels, occupation, landholdings) to show those schemes in its database that citizens are eligible for (eligibility is determined through a rule mapping algorithm that is periodically updated by the team).

HESPL trains local citizens, usually active at their village, Gram Panchayat or block levels, to use the platform. These trained field workers ‘Haqdarshaks’ (or Haqdarshikas, as they are majorly women) then go door-to-door and screen other citizens, explaining to them the entitlements they are eligible for and helping them apply for the same. Haqdarshikas charge a nominal fee from citizens for the services they provide. This allows the Haqdarshak model to operate not only as a last-mile access platform but also as an agent-based model that creates alternative livelihood opportunities for rural entrepreneurs.

Between January and March 2021, which also marked the second wave of Covid-19 in India, in Bihar and Uttar Pradesh, the Haqdarshak app was used for applying for social protection services like pension schemes. Citizens also used it to apply for essential documents such as ration cards and PAN cards. Between January and March 2021, the Haqdarshak platform helped more than 3,000 beneficiaries in Bihar, and 2,000 beneficiaries in Uttar Pradesh, apply for and receive their ration cards [1].

LEAD is currently undertaking a study to examine the impact of the platform in Chhattisgarh. The study aims to understand how the model promotes women’s economic and social empowerment and citizens’ access to entitlements.

GramVaani – The Mobile Vaani Network

GramVaani is a for-profit social tech company that has launched an initiative called the MobileVaani (MV) Network – an Interactive Voice Response (IVR)-based social media platform for rural and low-income urban households, low literacy regions, and non-Internet users. The benefits of an IVR platform include simplicity of use, no requirement for internet connectivity (hence, also serving internet dark regions in the tribal hinterlands of India), and no need for a smartphone. Users of this platform can record messages they want to share with their local community, listen to messages recorded by others, comment on and share other people’s messages, and navigate to different topics and location-specific channels.

In this way, the MobileVaani network promotes dissemination and awareness of locally relevant information and relies on local volunteers who help citizens resolve the grievances they share on the platform. Volunteers provide support with local advocacy, filing complaints, interacting with access points or escalating issues to local authorities on behalf of citizens. Analysis of complaints received on the platform and impact stories recorded by volunteers has allowed GramVaani to build a set of Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs) that local communities and civil society organisations can use to provide beneficiaries assistance with grievance redressal.

In Bihar and UP, between March and November 2020 (which marks the period of the first Covid-19 lockdown in India), a majority of the complaints that were recorded and resolved on the MV platform related to the Public Distribution System (PDS) and DBT schemes like pension, PM KISAN and PM Ujjwala Yojana. As this study suggests, volunteers helped citizens in these states resolve issues around processing applications and failures in receiving benefits under DBTs, issues of targeting and eligibility, and application-related problems like the inability to meet documentation requirements under PDS.

Expanding Administrative Capacity – The EasyGov Model

A smooth welfare delivery system requires sophisticated digital capacity, strong operational and financial management and a skilled workforce at local and national levels of bureaucracy. Improving administrative processes and empowering local bureaucracy with physical resources and skillsets is, therefore, crucial.

EasyGov, a for-profit start-up initiative, EasyGov works with state governments (having already partnered successfully with Karnataka, Bihar and Tripura, and with other state partnerships in the pipeline) to develop and provide white-labelled digital platforms [2]. These locally-oriented platforms, available in local languages and incorporating state-level schemes and services, can enable state administrative machinery to perform service delivery smoothly, efficiently, and in a coordinated manner.

- EasyGov’s platforms help state governments with the Enterprise Resource Planning (ERP) [3] of social welfare delivery, integrating the following capabilities in a single platform – service delivery, executive and management direction, operation management, and enterprise management [4].

- EasyGov platforms unify and automate the delivery of available benefits (and any new welfare policy initiatives that might be launched in the future) by leveraging technology. Automation to enable government at all levels to provide timely delivery of benefits distinguishes EasyGov from the more civil-society mediated and citizen-centric models like Haqdarshak and Gram Vaani.

- While the primary focus of EasyGov’s work is to improve government capacities for welfare delivery, it has also developed digital interfaces (both at the national level and for the states of Karnataka, Bihar and Tripura) that can be used by citizens to access information on government entitlements, check their eligibility for these entitlements and understand how to apply for them.

- Between April 2020 and March 2021, these platforms were used to gain information about a vast host of social protection schemes, including PM KISAN, PM Garib Kalyan Yojana And Ayushman Bharat, and documents like Aadhaar Card, Voter ID and PAN Card.

Generating Synergy: Exploring Pathways for Future Collaboration

These three models cater to three different but interlinked stages in the welfare delivery process – enrolment into welfare services ( hand-holding support with applications provided under the Haqdarshak model), grievance redressal ( local support for complaint resolution provided by MobileVaani volunteers), and the back-end processing of applications (EasyGov platforms created to streamline and integrate these processes).

Given their complementary nature, partnerships and coordination can help these models scale and reach a larger number of citizens. For instance, the Haqdarshak and MobileVaani models can be linked to administrative portals like EasyGov’s state platforms or other government-run portals like the E-district or CSC networks. This potentially allows the Haqdarshak model to inform both its agents and their customers about the status of their applications and any issues that may delay their benefits. Such information can be disseminated through periodic text-message based notifications sent out to agents and customers. For the MobileVaani model, such linkage can allow any complaints received on the platform to be routed to the relevant department through the administrative platform, thereby enhancing the capacities of their agents to resolve grievances.

Ultimately, it is also essential for these three models to be integrated into the government’s official welfare administrative processes. Integrating private initiatives like the ones discussed in this piece and other community-based institutions, civil society organisations, and social workers into welfare access and grievance redressal processes is vital to make them more accessible to citizens.

Looking Ahead

Access to social protection in India has acquired much more importance in the light of the Covid-19 pandemic. Platforms like Haqdarshak, Easy Gov and GramVaani can address some of the barriers that prevent citizens from accessing social protection, ensuring timely delivery of entitlements. Integrating the benefits of each platform with the social protection delivery chain and linking it with existing governance systems can help service providers tap into economies of scale.

A digital, platform-based approach towards social welfare delivery is not without its challenges, as technology cannot operate in a vacuum – and must consider co-abiding social and political factors.

As this OECD study suggests, private production of core ancillary services as in the case of the platforms discussed above, interoperability and private data ownership are important issues – and their regulation requires a strong governance framework. Ethical challenges include balancing the human component of social welfare with the technological and achieving a pace of digitization that is both acceptable to citizens and appropriate for the accomplishment of policy goals. Ultimately, the impact of tech-based initiatives may remain limited, unless local, state and central government processes and capacities are aligned with the shift towards digitisation.

Image: UN Women Asia and the Pacific/Flickr

Endnotes

[1] This data has been taken from a dashboard maintained by HESPL as it works in partnership with LEAD to deliver its model across various states in India during the Covid-19 pandemic.

[2] White label products are manufactured by a third party, not the company that sells/uses it, or necessarily even markets it. The advantage is that a single company does not have to go through the entire process of creating and selling a product.

[3] Enterprise resource planning (ERP) is a process used by companies to manage and integrate the important parts of their businesses.

[4] Based on insights gained from the team’s interactions with EasyGov representatives.

About the Authors

Bhaskar Pant is a Senior Consultant with the Financial Inclusion vertical at LEAD. He has advised multilateral institutions, senior politicians, policymakers in the Indian Parliament and non-profit institutions on a range of policy and regulatory issues, with a strong focus on technology.

Deveshi Chawda holds an M.Sc. in Behavioural Economics from University College Dublin in Ireland and did her B.A. (Honors) Economics from Shri Ram College of Commerce, University of Delhi.