Despite efforts from all quarters, 2 billion people globally are still excluded from formal sources of financial services. Digital financial inclusion has emerged as the new wave in the hope that it will reach the last mile consumer in the most convenient and affordable manner. In the context of India, digital financial inclusion is still a work in progress. As per the 2015 Financial Inclusion Insight survey, 49 percent of Indian adults are digitally included – i.e., they have digital access to a financial account. However, usage of these digital accounts remains debatable. Similarly, only 0.4 percent of adults in India use mobile money, primarily due to the key challenges of poor infrastructure and lack of financial know-how. The financial inclusion divide is even more glaring among poor women. Indian women are 8 percent less likely to own a formal financial account and 12 percent less likely to use digital services offered by these accounts. Digital modes of enhancing financial inclusion for women by targeting self-help groups (SHGs) could be one potential channel for accelerating and promoting digital financial inclusion in India.

SHGs as a development model can specifically benefit from digitization. A 2014 study by IFMR LEAD examining 200 SHGs across Karnataka, Bihar, and Madhya Pradesh found that while groups were diligent in recording meeting minutes, they found it difficult to regularly update SHG transaction information due to lack of resources and over-reliance on the few literate members in the groups. It was also found that group members did not have equal and complete access to financial information and that information was concentrated among leaders or secretaries of the groups rather than spread among everyone. Digitization of SHGs along with the use of mobile phones has the potential to solve these problems.

SHGs as a development model can specifically benefit from digitization. A 2014 study by IFMR LEAD examining 200 SHGs across Karnataka, Bihar, and Madhya Pradesh found that while groups were diligent in recording meeting minutes, they found it difficult to regularly update SHG transaction information due to lack of resources and over-reliance on the few literate members in the groups. It was also found that group members did not have equal and complete access to financial information and that information was concentrated among leaders or secretaries of the groups rather than spread among everyone. Digitization of SHGs along with the use of mobile phones has the potential to solve these problems.

For SHGs, digital financial inclusion can be targeted through two separate but symbiotically enabling core activities: recording of financial information digitally and facilitating transactions using digital, paper-less modes like mobile money, mobile wallets, debit cards, ATMs, and Epos machines. The interdependence between these two arises because facilitating transactions digitally can be sustainable and effective only if there exists an accessible database with financial information on SHG members, and, vice versa, digital information can be more cost effectively and seamlessly updated in the long run if transactions themselves are digitized. The push so far, has primarily been in the direction of recording digital information of SHGs. In this post, we focus on this first yet significant step.

Digitizing information about members of self-help groups and their group transactions in the form of internal and external loans come with certain inherent benefits. Primarily this has the potential to bring in accountability within SHGs and promote self-reliance in bookkeeping and group-level decision-making. It offers a cheaper and more secure alternative to storing and updating information on paper. It has the distinction of offering more convenience, both for self-help promotion institutions (SHPI) staff and SHG members, by removing the need to physically travel to deliver or collect information. It allows easy access for relevant stakeholders like banks, which can then make more timely decisions. In fact, it has the potential to provide detailed and reliable information to banks and credit bureaus about SHGs’ credit and transaction histories, making it easier to grade them accurately and provide them with requisite and responsible financial services. Finally, a digital platform with financial information about SHGs and SHG members can be used to expand the reach of government programs like the National Rural Livelihoods Mission (NRLM) and the Pradhan Mantri Jan-Dhan Yojana (PMJDY) targeted at improving financial inclusion and livelihoodsusing Aadhar linked identities of members.

Progress so Far

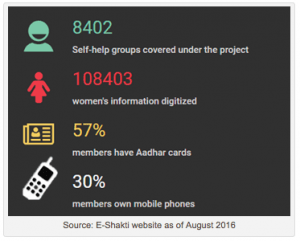

The National Bank for Agriculture and Rural Development (NABARD) has been at the forefront of pushing for digitizing SHGs’ financial information. E-Shakti (meaning electronic empowerment), piloted in two districts, Ramgarh in Jharkhand and Dhule in Maharashtra, so far has covered 8,400 groups across 1,110 villages. To date the results of the pilot have been promising, with imminent plans to extend the program to 22 additional districts. An interview with a sector expert and former official from NABARD confirmed that as a result of digitization, it has been observed that groups are getting increased funding from banks as banks have more access to data that allows them to more accurately grade SHGs.

Challenges in the Digitization of SHGs’ Records

The digitization of SHGs, however, has not been without several challenges that threaten to prevent the full actualization of its benefits.

- Data Quality: NABARD reports facing obstacles in gathering reliable data, in part due to the poor existing practices surrounding gathering data and maintaining records. Largely speaking, mechanisms that ensure data is being entered accurately are yet to be put in place with no protocol to double-check the data being entered in the systems.

- Process Delays: The recording of information is a time consuming, cumbersome process, especially at the outset of the digitization process, given the staggering amount of data there is to digitize. What’s more, this process is often slowed down by poor internet connectivity. For SHPIs working primarily with SHGs, customizing software to adapt to the workings of SHG models has been a major challenge, costing significant time and resources.

- Resource Constraints: In the long run, digitization programs are expected to be sustained by SHG members entering information on their feature or smart phones. Training of SHG members is required during the initial stages, and often beyond the initial stages data is still being entered in tablets by volunteers or loan collection officers in many instances. These tablets, while cost effective, are difficult to provide at a large scale, not to mention the resource constraints of relying on volunteers and loan collection officers. Entering data via smart phones and SHG members are the obvious first choice, but, mobile ownership among women remains low. SHPI’s like Hand in Hand, India are overcoming this problem by designing innovative loan products, such as loans to buy mobile phones.

- Stakeholder Cooperation: To fully realize the benefits of digitization, it must be expansive both “horizontally” and “vertically”. Horizontally, it requires the cooperation of all members in all SHGs across the country, and vertically, all the stakeholders – SHPIs, banks and credit bureaus – must be on board in order to realize the benefits of going digital. Though challenging, bringing all the relevant stakeholders on a common platform would help make the transition from manual to digital collection of information remarkably efficient.

These challenges, while significant and deserving of attention from policy makers and implementers, are not insurmountable. It has to be understood that digitizing existing information is an initial fixed cost, after which updating can be orchestrated at a minimal periodic cost. As mentioned, digitization of records helps address accountability and transparency concerns, and it also opens the doorway towards facilitating and enabling SHGs to digitize their financial transactions and function with less cash. Digitization of SHG records and transactions should thus be viewed as interdependent functions rather than viewed in isolation to each other. Organizations such as Payse are piloting digital hardware wallets to digitize records and transactions, wherein all the SHG leaders are provided with a Payse hardware wallet called PURSE which is used to convert c

ash to e-money and store it for repayment with the help of an agent. Although this is currently being implemented on a small scale, this is a step in the right direction.

The Way Forward

Technology can play a vital role in facilitating greater outreach of financial services for the rural and urban poor, and especially for women. While the Government of India has taken positive steps towards bringing SHGs into the ambit of digital financial inclusion, there is a considerable lack of research in understanding what works and what doesn’t. NABARD has worked in close collaboration with several implementing agencies to better understand these challenges. However, additional short term and pilot studies assessing the impact of digitizing SHG records on penetration and usage of financial services and on other socio-economic indicators would be beneficial in taking stock of the types and extent of externalities this switch to digital creates. There is also a need to conduct qualitative assessments from the supply side to better understand the constraints that financial service providers face in making SHG transactions digital. These outstanding uncertainties are imperative and urgent at a time when NABARD and SHPIs are looking to expand their digitization efforts nationally. Quantitatively supported, timely insight into what works in implementation has the potential to resolve issues to fully realize the benefits of digitization for all the stakeholders in the self-help group ecosystem.

Featured image: ADFIAP