Policy makers are interested in increasing returns from education to the society and not just the individual. When thinking about how an increase in school quality could result in increased earnings to the society, we need to take other factors into consideration. For instance, for a given cohort we may find that there are a limited set of jobs available. If one individual from the cohort secures a job, it comes at the expense of another individual. So what may be beneficial to individuals may not be beneficial to the society. Economists call this the ‘equilibrium effect’. One must also recognize that policy makers often have limited resources and a large number of alternative interventions that have shown to cause an increase in returns to education. For instance, Heath and Mubarak (2013) find that the exponential growth in the garment manufacturing sector in Bangladesh has had a larger impact on returns to education than the conditional cash transfer program that incentivizes households to send their children to school. Economists would argue that the reason behind the differences in impact of both interventions is because the real binding constraint lies in the labour market. From the policy point of view, this is an important piece of evidence that allows policy makers to choose the right intervention amongst alternatives. I discuss below how each of these factors needs to be measured, and their individual coefficients compared in order for us to be confident about the importance of interventions concerning school quality in improving social returns to education.

Equilibrium Effects

Binding Constraints

etween contending alternatives, it is always useful to ask if the intervention is addressing the binding constraint. This would allow the policy makers to decide whether they should be investing in improving the quality of education or in other alternatives. I provide here examples of studies that should be of interest in the Indian context because they are able to credibly address the question of external validity and find large effects from externalities. But the list is by no means meant to be exhaustive.

i) Technology – Indian government introduced modern agricultural technology as part of the ‘Green Revolution’ in 1963. Considering the appropriate utilization of the new technology required the farmers to be literate, Foster and Rosenzweig (1998) study the impact the policy had on returns to education. They find that introduction of technology resulted in an increase in the returns to education. The study describes how the new technology increased the demand for education causing the overall returns to the society to rise. This is an example of how demand side interventions could possibly impact returns to education.

ii) Labour market opportunities – There are a variety of studies that try to explore the impact of the growth in the Information Technology Enabled Services (ITES) in India on the demand for education. These demonstrate how growth in labour market opportunities can result in an increase in returns to education. Oster and Steinberg (2013) find that the presence of an ITES company in the vicinity causes an increase in enrollment rates locally. Munshi and Rosenzweig (2006) find that lower-caste girls opt for English medium schools if there is a presence of ITES in the area of their residence. Jensen (2012) in an experimental study finds that there is an increase in the number of years of schooling if the community is made aware of the ITES opportunities available. But the key here is to focus on high skilled labour opportunities. Atkin (2012) finds that growth in low skilled manufacturing jobs in Mexico results in a fall in years of schooling. This suggests the increase in low-skilled jobs in Mexico made the opportunity cost of leaving school very lucrative. Altogether, these studies point towards the possibility of high-skilled labour market opportunities in improving returns to education.

Conclusion

From the above discussion, we can safely conclude that while the evidence currently available on learning outcomes is both valuable and encouraging, it is far from sufficient to frame evidence-based education policies in India. Given the numerous areas that can be affected by education policies, we still need much more evidence. Evidence looking at the role of labour market effects, and technology in determining educational outcomes, and the magnitude of their coefficients are possibly of immediate interest in this respect. While RCTs could provide us answers to many of these questions, a pooled panel data at the sub-regional level may do better in answering questions concerning equilibrium effects, and identifying binding constraints. It is also possible that different parts of India require different sets of constraints to be assessed given the variation in institutional environment.

|

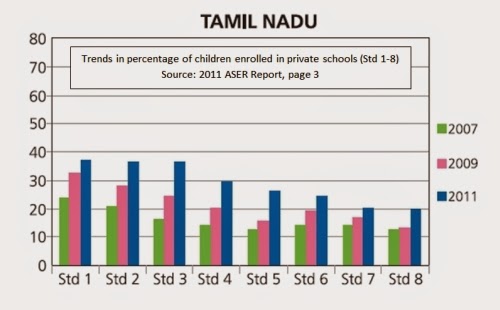

| Source: 2011 ASER Report |

Yale Economic Growth Center’s Tamil Nadu Socioeconomic Mobility Survey is uniquely placed in this context, as it is a data set that collects information, not only on households and individuals, but also community institutions. As it is data from within a state, it allows one to be less concerned about large variations in an institutional environment. The data is interesting as it also contains data on time-use for women, local prices and wages, local infrastructure along with household and individual data. In a sense it is able to combine features that are otherwise present in disparate surveys such as the Annual Survey of Industries, Time Use Surveys, National Statistical Sample Surveys, etc. This provides for a great possibility for interesting work on education, allowing us to answer many of the questions raised above.

Atkin, David. (2012) “Endogenous skill acquisition and export manufacturing in Mexico”. No. w18266. National Bureau of Economic Research.

Banerjee. R, Bhattacharjea. S. and Wadhwa. W, (2005) “ASER Reports”, ASER Center, New Delhi.

Chetty, Friedman and Rockoff, American Economic Review 104(9): 2633-2679, 2014

Duflo, Esther. 2001. “Schooling and Labor Market Consequences of School Construction in Indonesia: Evidence from an Unusual Policy Experiment.” The American Economic Review 91 (4).

Foster, Andrew D. and Mark R. Rosenzweig. 1996. “Technical Change and Human-Capital Returns and Investments: Evidence from the Green Revolution.” The American Economic Review 86 (4):pp. 931–953.

Fulford, S (2014), “Returns to Education in India”, World Development, 59: pp. 434–450.

Heath. R. and Mubarak. M. (2013), “Manufacturing Growth and the Lives of Bangladeshi Women”, Working Paper. JEL CODES: O12, F16, I25, J23

Heckman, James J & Lochner, Lance & Taber, Christopher, 1998. “General-Equilibrium Treatment Effects: A Study of Tuition Policy,” American Economic Review, American Economic Association, American Economic Association, vol. 88(2), pages 381-86, May.

Jensen, R. 2010. “The (Perceived) Returns to Education and the Demand for Schooling.” Quarterly Journal of Economics 125 (2): 515-548.

Munshi, K., and M. R. Rosenzweig. 2006. “Traditional Institutions Meet the Modern World: Caste, Gender, and Schooling Choice in a Globalizing Economy.” The American Economic Review 96 (4): 1225-1252.

Oster, E., and B. M. Steinberg. 2013. “Do IT Centers Promote School Enrollment? Evidence from India.” Journal of Development Economics 104: 123-135.

PROBE Team, The. 1999. Public Report on Basic Education in India. New Delhi: Oxford University Press.

Psacharopoulos, George and Harry Anthony Patrinos. 2004. “Returns to investment in education: a further update.” Education Economics 12 (2):111–134.

Project Summary- Yale Economic Growth Center’s Tamil Nadu Socioeconomic Mobility Survey