South Asian economies primarily depend on agriculture for employment, with nearly 1.5 billion people directly dependant on the sector. However, in recent times, changing climatic conditions are impacting agricultural productivity, through temperature changes and water availability. Smallholder farmers in low- and middle-income countries such as Nepal, India, Pakistan and Bangladesh are severely affected by these changes due to poor infrastructure, limited access to both local and global markets, low productivity, and lack of access to formal safety nets. As South Asian countries confront increased vulnerability to climate change, there have been several policy efforts focused on initiating several climate resilient agricultural practises and policies.

Climate-Resilient Agriculture is defined as “agriculture that sustainably increases productivity, resilience (adaptation), reduces/removes GHGs (mitigation), and enhances achievement of national food security and development goals”.

Most of these practises aim at a “triple win” by targeting the three outcomes of enhanced productivity, resilience and carbon sequestration. Though the benefits of adopting these practises are well-known and transparent for the farmers, the uptake of these practises has been very low. Despite government support and initiatives, adoption of practises have not been homogeneous across geographies and rarely at scale.

Against this backdrop, it becomes important to understand the barriers to uptake and adoption, and potential strategies to address these barriers. In this blog, we highlight insights on adoption and barriers to adoption from a transboundary study undertaken by LEAD and ICIMOD in India and Nepal.

Does adaptation of CRA practises vary across borders?

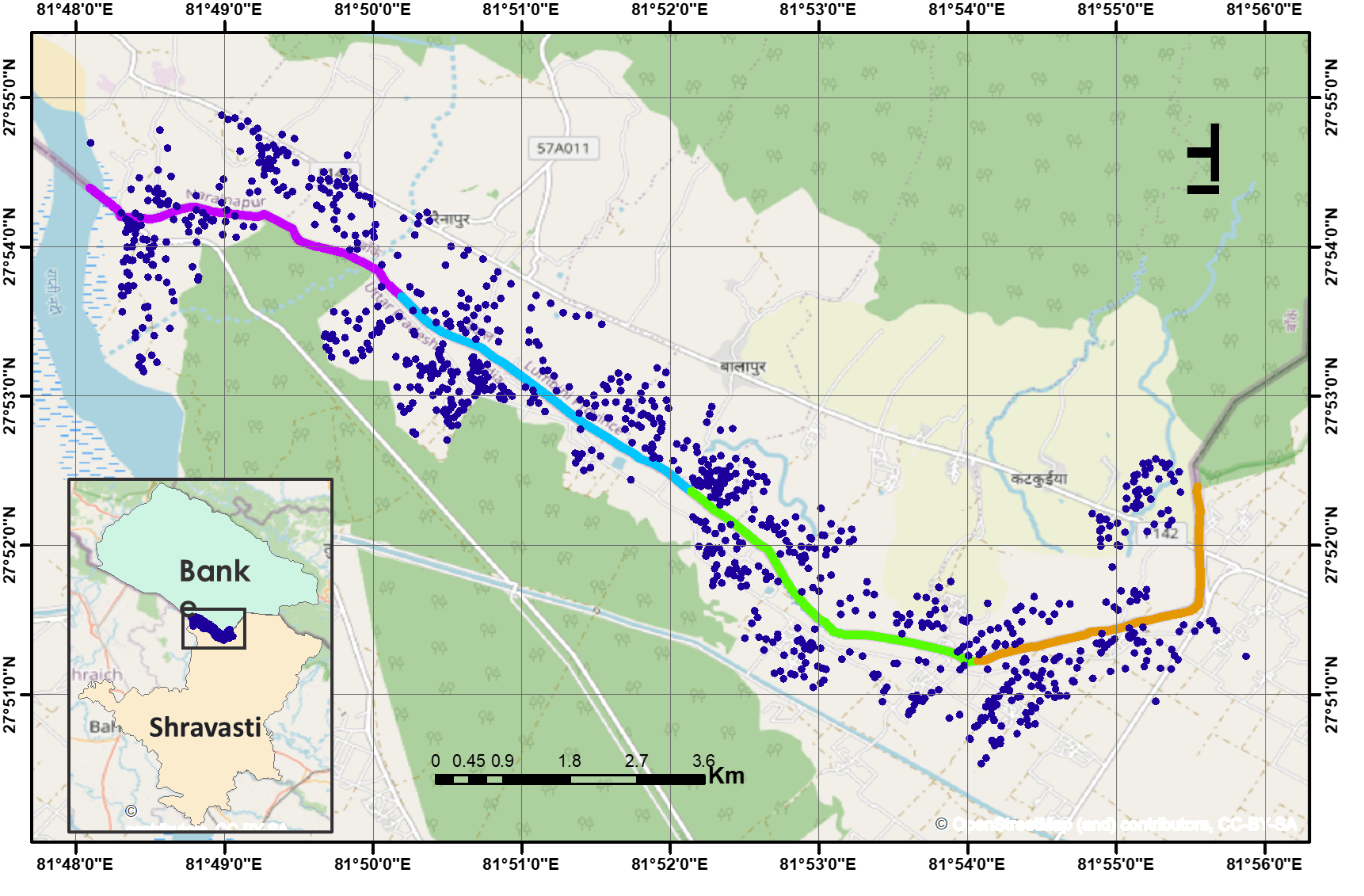

The farmers selected for the study were from the border regions of India (Uttar Pradesh) and Nepal (Banke). Are there any variations in the adaptation of CRA practises with spatial variations?, i.e, how do the farming households across borders, exposed to different policy regimes, respond to CRA practises? What can the governments do to unify these efforts and gain mutually in building resilient communities?

Data Source: OpenStreetMap (OSM), IndoNepal Border (Line): Digitised District boundaries: open source administrative boundaries and survey data

How are the farmers adopting?

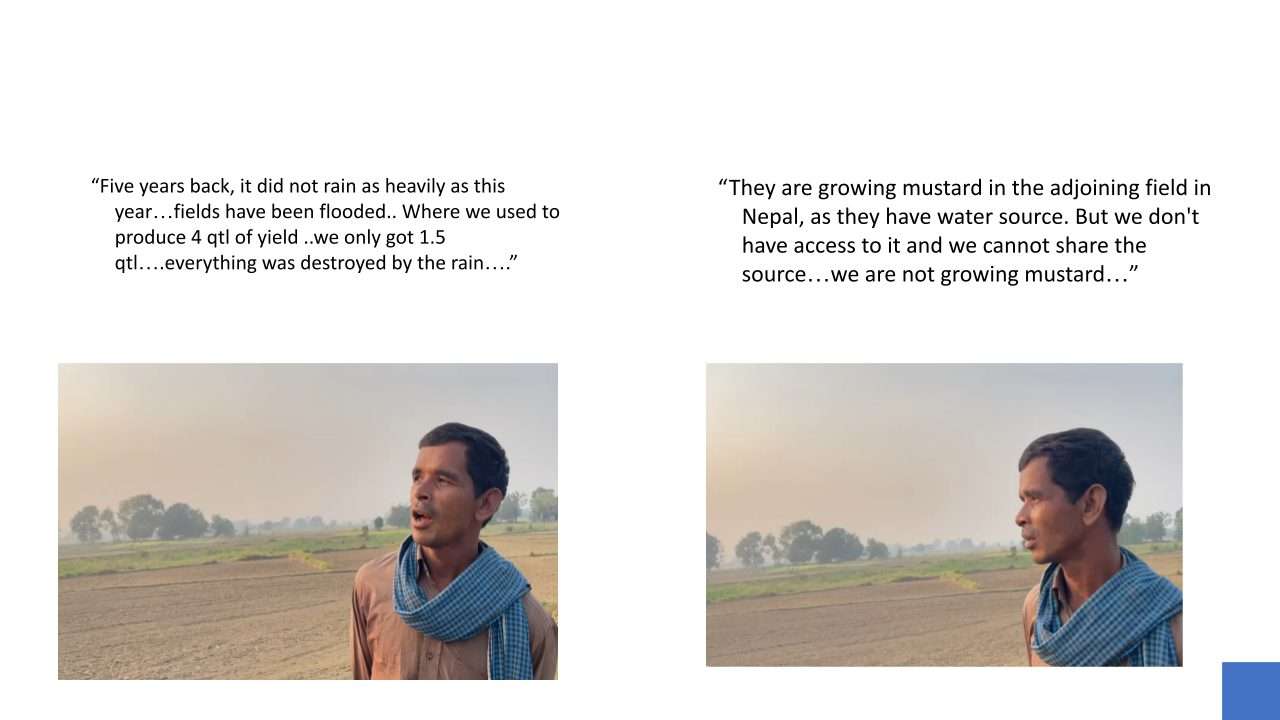

Picture: LEAD at Krea University

We find a lot of variation in both awareness and adoption of CRA practises among farmers in both countries.

- While there is high awareness among farmers regarding soil-related practises like reduced fallows, weeding, harrowing, and use of organic manures among the farmers in India; the adoption is higher for reduced fallows, weeding and use of organic manures.

- In Nepal, we find the farmers are aware of a higher number of practises than in India, with higher awareness on crop rotation and use of organic manures, wherelse the adoption is only high for crop rotation as compared to all other available practises. The gap between awareness and adoption also suggests that it is vital to understand the non-information/knowledge barriers like credit, infrastructure, social and economic barriers.Over 64% farmers in India and Nepal reported decrease in water availability in the last 5 years.More than 50% and 70% farmers in India and Nepal respectively cited droughts and more than 50% farmers in both the countries cited depletion of ground level water as a primary cause for reduction in water availability.

- Overall, the awareness and adoption of water related practises is low among the farmers in both the countries, with only the farmers in India reporting a little higher adoption of water related practises like small scale reservoirs and farm ponds. Most of the adoption was driven by either enrolment into policies like Krishi Sinchai Yojana (Irrigation scheme) or driven by support from NGO’s and FPO’s. The low adoption of irrigation facilities is not very surprising given adoption of irrigation is expensive and often requires farming scale and technical expertise along with capital requirements which small farmers lack.

- Similar to soil and water-related practises, we find very low awareness among farmers regarding crop-related practises. This has also resulted in low adoption of crop related practises as seen in other regions as well, with exception to use of intercropping mixed cropping, and hybrid and traditional seeds in Nepal.

Picture: LEAD at Krea University

What are the barriers to adoption ?

Picture: LEAD at Krea University

For crop and soil related practises that have a higher adoption rate as compared to water related practises, we find that the majority of farmers cited lack of financial, credit and subsidy as a major constraint to adoption.

Firstly, access to credit remains very low with farmers needing to travel anywhere between 5 to 35 kms to reach the nearest financial institution. Secondly the farmers who did avail credit used it partially or fully for non-agriculture related expenses. This highlights a huge gap in essential financial products that are able to meet all kinds of financial needs of the households( both personal and agricultural) like education, marriage, health expenses etc.

Similarly, access to extension services, like KVK(krishi Vikas Kendra) in India and AKC( Agricultural Knowledge Centre) in Nepal was abysmally low for farmers (30% in India and 11% in Nepal). The extension service centres were also located at an average distance of 24 km ( 1- 45 km) in India and 27 Km (1-55 km) in Nepal. Majority of the farmers (94% in Nepal and 89% in India) were not a member in any community or farmers organisations/institutions like FPO, FPG,PACS, etc.; or use any available mobile apps like geokrishi, Hamro krishi etc.; further constraining them from availing benefits of either knowledge or awareness regarding new technology, easy credit availability and enrolment to various government schemes. This also explains the poor enrolment rate of farmers into various available policies and schemes even when a farmer is aware about a particular scheme.

For the farmers in India where the enrolment into government policy and programmes was higher (89% farmers did not enrol into any policy or scheme), we found most of the farmers enrolling into Pradhan Mantri Kisan Samman Nidhi, Beej Gram yojana in agricultural scheme and; SRLM, Indira awas Yojana, National food security scheme, PDS in non-agricultural schemes. There was very low enrolment into agricultural insurance schemes both in India and Nepal.

Call for Policy Convergence

Picture: LEAD at Krea University

The insights from the study can inform policy efforts that seek to link local and sub-national policies with transnational initiatives, by understanding the common barriers to adoption such as knowledge, information, awareness, extension services, credit as suggested by the findings. Currently, farmers rely on neighbouring farmers, so institutional and community-based information should be delivered so that information is fairly and equally disseminated. Irrespective of geographic boundaries and political setups, exchange of information among the farmers by organising joint workshops, meetings, and discussion on best practises should be encouraged. Ground level organisations should be encouraged to do so, with proper monitoring and guidance from extension services. Enrolment into policies and programmes effectively can boost adoption as witnessed in case of the farmers in India or adoption of best practises like organic farming and use of resilient traditional seeds in Nepal. The salient features of successful schemes should be exchanged between the nations, calling for a transboundary governance solution to transboundary problems across South Asia.

Cover Image: LEAD at Krea University

About the Author

Sabina Yasmin is a Senior Research Fellow at LEAD and currently also serves as a Bharat Inclusion Fellow. Her research interests include agricultural economics, rural finance, development economics and applied microeconomics. Sabina is immensely passionate about using her work for the upliftment of marginalised people. Prior to joining LEAD, she taught economics to engineering and social science students at SRM University-Amravati.