As the second wave of the COVID-19 pandemic gripped India and the world in early March 2021, discussions about vaccination inequities, and reopening schools and public spaces caught our attention once again.

Social media, particularly the Twitterverse, was inundated with debates between epidemiologists, public health experts, economists, and armchair experts. Emily Oster, an economist at Brown University, and a strong advocate for using data to guide the decision of reopening schools in the US, found herself in the middle of a heated debate about the masking mandates for children. The incident has called attention to the need for including different stakeholder groups in the conversation about evidence that is crucial for combating health risks and improving the impact of policy measures directed at creating sustainable livelihoods, enabling access to education, and other essential services, and demystifying what the data says.

Building institutional bridges

Building trust and engagement with policy stakeholders is a high-touch exercise and establishing new connections can be challenging amidst a pandemic, with existing government resources being over-leveraged. Bridging this evidence-policy interface requires significant efforts even under normal circumstances – and the current scenario has further demonstrated these complexities, particularly in countries that lack the tradition and institutional support structures to facilitate such an exchange.

For instance, in the United Kingdom, the What Works network uses evidence to improve the design and delivery of public services. In the context of COVID, the ‘Rebuilding a Resilient Britain’ initiative was a comprehensive exercise to map priority evidence gaps across areas of research.

WHO has set up the Evidence-informed Policy Network (EVIPNet), a knowledge translation platform that aims to institutionalise country capacity for informed decision-making. Its recent global conference on communicating research during health emergencies explored some of these questions across disciplines.

Early empirical research from Australia has also demonstrated the importance of effective communication, which is embedded in building trust, and informed by a continuous engagement between stakeholders. In 2020, a group of researchers began testing a portfolio of interventions to increase mask-wearing at a large scale in Bangladesh. Preliminary results suggest that free mask distribution and promotion, at the household and community level, increased the number of people who wore masks and adhered to physical distancing guidelines. While discussions about generalizability and external validity of the results continue, one can argue that the research coalition’s collaborative approach, built on robust communication with various local actors and stakeholders, is one of the key success factors in rolling out the intervention early and informing the government’s strategy. The team is working on building coalitions in other countries such as India, Pakistan, and now Latin America to scale the model.

Mexico’s National Council for the Evaluation of Social Policy (CONEVAL) is another good example of institutionalising evaluations and creating a vibrant community of practice.

While there is no dearth of credible research organisations in India, questions about institutional and individual capacities to build these connections loom large. For instance, the Development Monitoring and Evaluation Office (DMEO), an attached office of NITI Aayog, is working on building the M&E ecosystem in India. The DMEO has the potential to take on a larger mandate – by introducing standards for M&E, and engaging a wider group of government and external stakeholders in the process. Moreover, there is an increasing role for boundary actors (‘knowledge brokers’) who can traverse disciplinary boundaries and walk the thin line of balancing and aligning stakeholder interests and engage in co-production and syntheses of knowledge.

LEAD’s own experience has demonstrated the importance of building trust and credibility through sustained engagement, embedded in the work of national, state and local actors, and having our ears to the ground – to be able to support the demand for data and evidence. For instance, LEAD’s STREE initiative is providing technical assistance to the National Rural Livelihoods Mission. As part of this collaboration, LEAD conducted a rapid study of the impact of COVID-19 on women-led enterprises across four states: Bihar, Chhattisgarh, Madhya Pradesh and Odisha. In Tamil Nadu, LEAD is also collaborating with the World Bank and Tamil Nadu Rural Transformation Project to assess the impact of the state’s COVID assistance programme.

As the immediate health crisis abates, researchers and allies also have an opportunity to support policy efforts to “restore, rebuild, and recreate” in the near and long term.

Embracing digital spaces

Travel restrictions and social distancing guidelines have forced us to move our interactions online. The dynamics of organising knowledge brokering exercises virtually may be entirely different. But these new spaces also open up the possibility to challenge conventional norms of engaging with policymakers, ease access, and bring new voices to the discourse. For instance, in a recent webinar series organised by IWWAGE – an initiative of LEAD at Krea University, Self-Help Group members from different states in India, had an opportunity to share their lived experiences and insights from supporting COVID relief and recovery efforts on the ground.

At the same time, these interactions highlight existing communication inequities within the ecosystem. While the use of digital platforms in the public sector is catching up, there is a need to bridge the digital access and capabilities divide in a country as diverse as India and provide frontline agents, block and district-level representatives an opportunity to participate in these forums.

From strategic to synergistic communication – how do we build this capacity?

A growing number of policy and impact fellowships in India are looking at preparing young talent for such engagements – looking beyond specialised skills. While development professionals are all too familiar with the catchphrase ‘strategic communications’, this kind of engagement goes beyond developing tailored strategies or leveraging innovative marketing tools and social media.

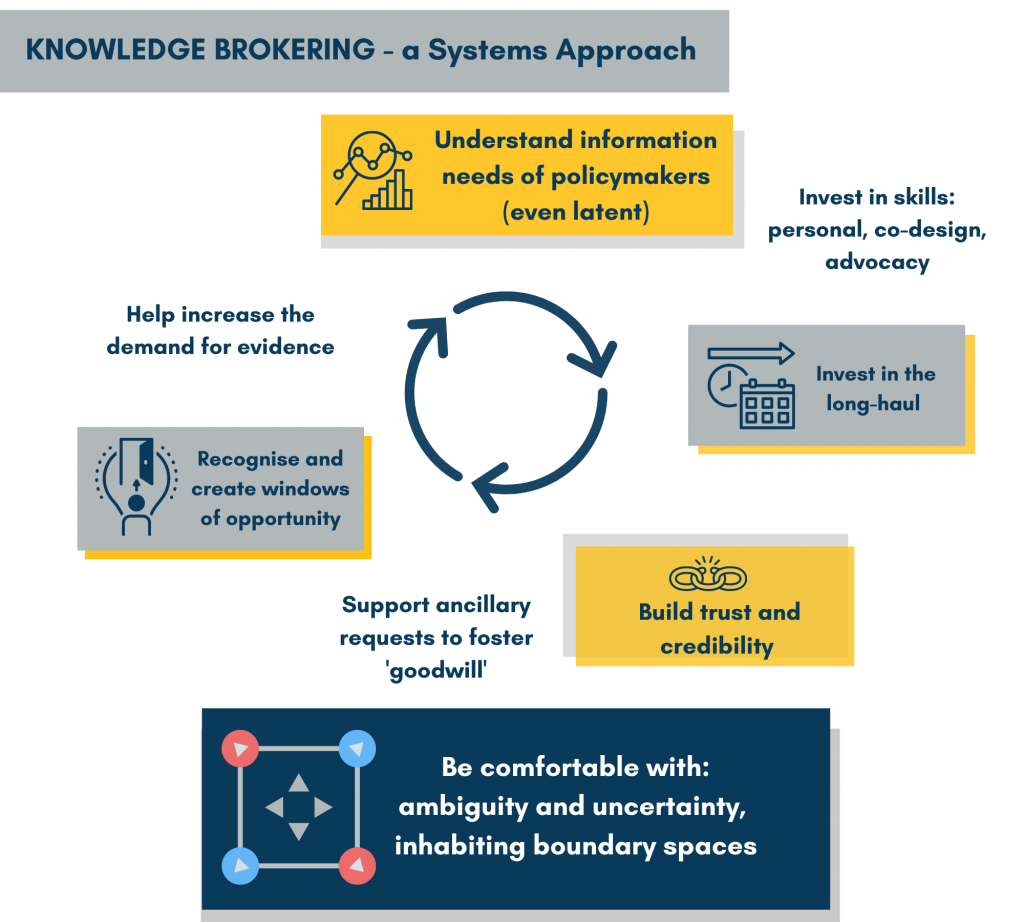

While this remains a relatively under-studied area, new research based on a study of 346 organisations working in the research-policy interface highlights how linear, relational and systemic approaches can work in different ways.

Knowledge brokering requires wearing many hats and an entrepreneurial mindset:

- Helping increase demand for evidence – understand the information needs of the policymaker, even when they may be latent (Topp et al, 2018)

- Recognising and often creating windows of opportunity

- Investing in the long-haul of policy engagement, by building trust, credibility and often supporting ancillary demands that may not be directly related to the research program

- Being comfortable with ambiguity and uncertainty and inhabiting boundary spaces

Moving the needle

“Many organizations talk about collaboration, co-design or co-production, but there is little clarity on what these terms mean in practice and what the role of researchers should be”.

Hopkins et al, 2021

Building individual and institutional capacity to facilitate evidence uptake in the Global South is important in the long-term, but the current crisis has also raised questions about how evidence is funded, generated and disseminated. It calls for a renewed focus on research to impact pathways, and investing in country capacities for informed decision-making.

In the Indian context, more attention needs to be paid to understand what forms of engagement between researchers, knowledge brokers and policymakers are most effective.

What data and evidence do decision-makers need right now, to act decisively? How do we navigate existing and new spaces better?

Allies such as funders have an important role to play in aligning research incentives and building bridges that will enable meaningful knowledge exchanges. During a crisis like COVID, policymakers and government bodies must explore unconventional ways of working – by keeping communication channels open and working with the research community to identify priorities. Finally, researchers need to reflect on the dynamic skills required to contribute to policy priorities, and recognise the potential and limits of different forms of engagement.

Featured illustration: Nirupama Francis

About the Author

Diksha Singh heads LEAD’s learning and communications portfolio. Trained as a researcher, she is passionate about connecting the dots between research, policy and impact. Diksha has more than a decade of experience in research, outreach and communications. She serves on the Board of Directors of SEEP Network. Prior to joining LEAD, she worked as a project officer with Praja Foundation, and as an analyst with CMIE. Diksha has a Master’s in Economics from the University of Mumbai.