From local kirana stores to home-based food businesses, handicraft clusters to small manufacturers, MSMEs are a cornerstone of India’s growth story. MSMEs create employment at scale and are an integral pillar of their local communities. COVID-19 and the resulting lockdown has adversely impacted the sector in India and compounded the challenges faced by microbusinesses, which have been particularly hit hard.

As part of MSME Week, we take a closer look at the challenges faced by microbusiness owners across India through this photo essay.

Rajni, 42, irons clothes for a living from her small neighbourhood shop in New Delhi. “I have not earned anything in over two months.” The business has dried up since the lockdown. Several NGOs and community-based organisations have initiated relief efforts across Delhi to help families affected by the lockdown. True to her working-class values, Rajni is hesitant to accept help. “We are poor, but we cannot beg.”

Money is not Rajni’s only concern, however. Reminiscing about life before the COVID-19 crisis, “I remember a time when we were invited into homes to share a cup of tea.” Microbusinesses like Rajni’s are an integral part of their local communities – deeply embedded in their social and economic fabric. The physical distancing guidelines in the wake of COVID-19 have altered the nature of interactions between small business owners and their customers, and affected their businesses adversely.

Image: Christopher Glan/LEAD at Krea

Payamala 60, and Kannamma, 55, are vegetable vendors who ply their trade on the streets of Chennai. Hailing from Vilamuthur, a village in the Perambalur district of Tamil Nadu, the couple are migrants who moved to Chennai in search of work. Like hundreds of vegetable vendors in the city, Payamala and Kannamma rely on the Koyambedu wholesale market for their supplies. In the wake of the COVID-19 crisis, the market cluster emerged as a major hotspot for the disease, causing major disruptions in supplies. As a result, the couple was forced to shut shop for two months and dip into their meagre savings.

The Tamil Nadu government has announced financial support of Rs. 1,000 in addition to free food supplies for all ration-card holders. As their Aadhaar and ration-cards are registered on their permanent address in Vilamathur, they have not received these benefits. With lockdown restrictions easing, the resilient couple is back in business. Despite these hardships, they are hopeful that business will return to normal soon as vegetables are an essential commodity.

Image: Kanika Joshi//LEAD at Krea

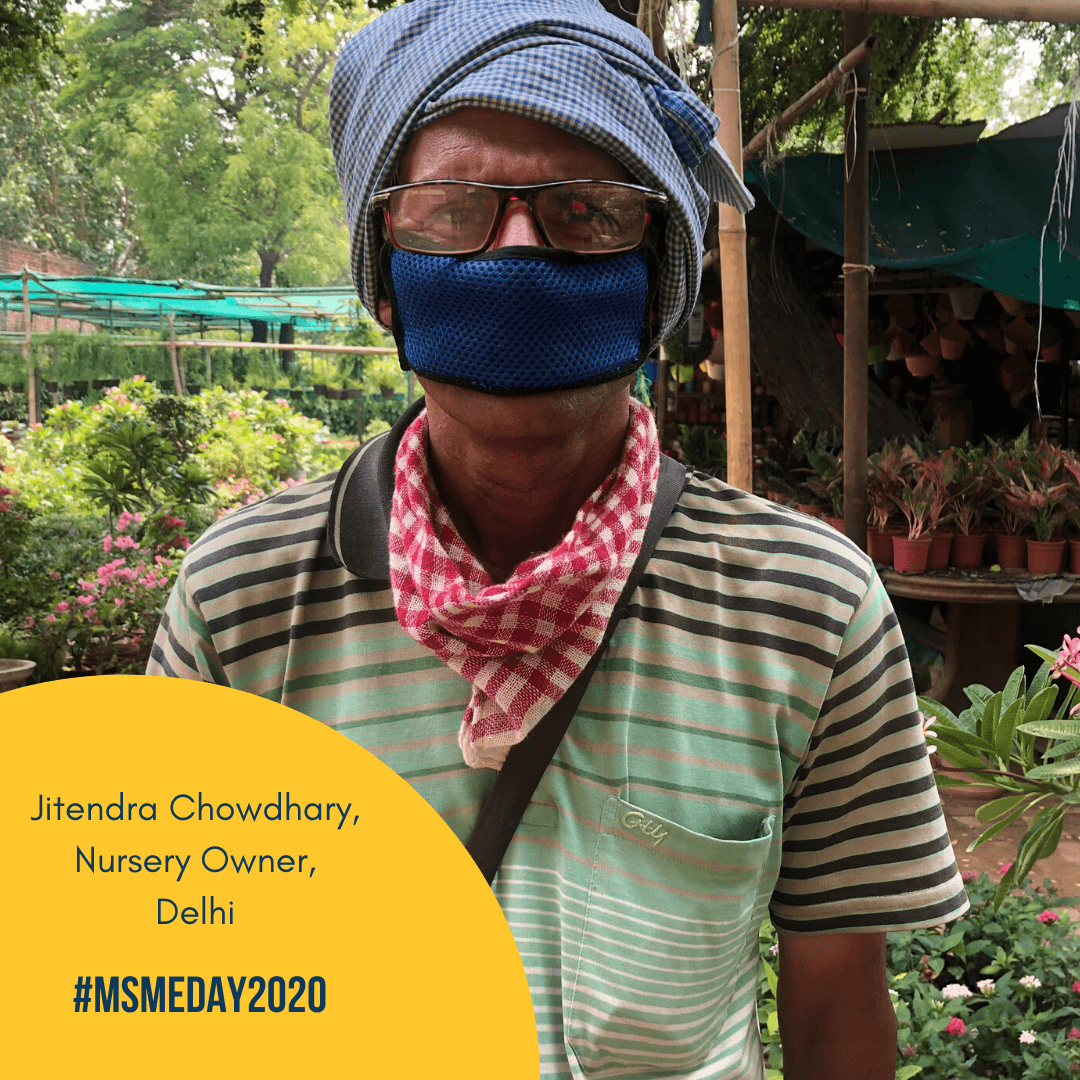

Jitendra Chowdhary, 55, runs a small nursery in Delhi. He is one of the 63 lakh migrants who now call the city home. Originally from Bihar, he moved to the national capital with his family fifteen years ago.

Business suffered considerably during the lockdown, as he does not sell essential commodities. “My shop used to be crowded like a mela. But now, I am lucky if I get even a single customer in a day.” Restricted movement during the lockdown period meant that Jitendra could no longer visit his beloved nursery and care for his plants. Despite the lull in business and drop in income, Jitendra’s first thought goes towards the poor unskilled labourers struggling to afford a single meal. “At least I have food on my table.” His family is being helped by a local NGO which distributes food in his locality. With the city slowly crawling back to life, Jitendra hopes to see his shop crowded with customers once again.

Image: Kanika Joshi//LEAD at Krea

Anju, 48, runs a tailoring kiosk in Noida. Even before the #covid crisis hit, her business fluctuated on a daily basis. Now, the single mother of two is caught in a ‘lives vs livelihood’ dilemma. When the lockdown came into force, Anju had to shut shop. Her son, who was employed with an automobile manufacturer, lost his job as well. Anju has borrowed money from the local kirana store to tide through these difficult times. “How much longer can I rely on the kindness of others?”, she wonders.

Business has been slow since she opened her shop again. Eager to support her family, Anju is now stitching masks to cater to the increasing demand. ‘”I am selling these masks for Rs.40 a piece. Even 40 rupees a day is better than having no income.”

Image: Kanika Joshi//LEAD at Krea

Salim Alam, a vegetable vendor in his forties, calls Delhi his home. He moved to the city from Bihar fifteen years ago in search of a better life. The national capital region attracts migrants from far-flung areas, accounting for a third of all migrants in the country. Like most small vendors, the lockdown has been especially hard for Salim’s family of six. His vegetable stall suffered due to a sharp decline in customers, compelling Salim to adapt and find alternative ways to reach customers. He now sells vegetables from a roving cart, in the punishing Delhi summer. Ramzan (19), his eldest son, lends a helping hand. The duo has been saving up for a bigger reason – Salim’s wife suffers from bad knees and thyroid. He has little faith in government hospitals, and wants to get her treated at a good facility, which unfortunately will not come cheap.

Having left their homes in search of better opportunities, millions of migrants like Salim face a dire situation today.

The family received financial assistance of Rs. 1000 from the Bihar government. “I feel let down. I have given fifteen years of work to the city of Delhi, but it was my home that came to my aid in these dire times.” Ramzan, however, remains optimistic. With lockdown measures easing and business slowly picking up, he hopes to save enough money for his mother’s treatment.

Featured Image: Kanika Joshi/LEAD at Krea