The adoption of the human right to water and sanitation by a resolution of the United Nations General Assembly in July 2010 helped ensure that a human rights perspective is integrated into the design and delivery of water, sanitation and hygiene programming. Global experiences, however, suggest that it has been difficult to fulfil the right to sanitation and uphold equality and non-discrimination as foundational principles of human rights law. In regions where sanitation gaps are highest, severe disparities in access are particularly evident among vulnerable groups, with women suffering in “gender-specific ways when they face obstacles in accessing sanitation facilities”[1]. To address these inequities and mainstream gender needs within national policies and practice, Goal 6.2 of the Sustainable Development Goals specifically advocates for “access to adequate and equitable sanitation and hygiene for all, paying special attention to the needs of women and girls and those in vulnerable situations”.

Menstrual hygiene is an important dimension of this global development framework to eliminate gender inequities in sanitation and hygiene. In the last decade, formative research on social attitudes, norms and practices around menarche and menstruation has highlighted the existence of deep-seated cultural taboos, beliefs, myths and a general lack of knowledge associated with menstruation in certain developing regions and communities [2,3,4,5]. Globally, there is a growing understanding that these practices, which mainly stem from a lack of awareness around menstruation, can perpetuate stigma, discrimination and even violence against women and girls, and carry adverse impacts on their psychosocial and physical health, education and economic outcomes.

Restrictive norms, archaic practices

In the Indian context, data from the 2011 Census suggests that approximately 54.5 per cent of the female population is in the reproductive age of 15-49 years and needs safe menstrual hygiene practices. Research literature indicates a considerable lack of knowledge and restrictive social norms and practices around menstrual hygiene among households and communities in India, with adverse impacts on women and adolescent girls [6,7,8,9,10]. According to data from the National Family Health Survey – Round 4 (NFHS-4), only 58 per cent of women and girls in the age group of 15-24 years use hygienic methods of menstrual protection. NFHS-4 also suggests urban-rural disparities in the use of improved menstrual hygiene practices.

Consistent with this evidence, in a recently completed study by LEAD on menstrual hygiene practices among women in the 20-50 year age group, we found that only 48 per cent of the 785 respondents reported using improved modes of menstrual protection such as sanitary napkins. The use of improved modes of protection was considerably higher among the younger age cohort of 20-30 years (86.9 per cent) than among the older cohort of 40-50 years (18.8 per cent). Over 88 per cent of respondents reported not having visited doctors for urogenital infections and the prevalence of doctor visits was higher among women who use unimproved modes of protection such as cloth (16.8 per cent) than among those that used improved modes such as sanitary napkins (5 per cent).

Consistent with past evidence on restrictive social norms and practices around menstruation, reported restrictions among our study respondents included – missing work or school (29.6 per cent), avoiding physical contact with household members (35 per cent) and avoiding religious places (94 per cent). Respondents from select villages also noted that it was common practice for women to stay in village public houses during their monthly menstrual cycle. 92.4 per cent of our women respondents did not report a preference to change their current mode of protection and a majority cited habit (63.7 per cent) and ease of use (54.6 per cent) as reasons for their current preference. However, despite their stated use and preferences, women of all ages were more willing to shift to improved modes of protection when they received free sanitary napkins through government programmes.

Role for Policy

India’s policy context for sanitation under the Swachh Bharat Mission (SBM) recognizes the importance of adopting a gendered perspective and approach to sanitation delivery and even articulates clear gender objectives. These include ensuring access to sanitation facilities that cater to the needs of women, promoting awareness around safe menstrual hygiene practices and developing economic models to meet the demand for sanitary napkins. Initiatives such as the Rashtriya Kishor Swasthya Karyakram of the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India actively support the health needs of adolescent girls, including menstrual hygiene management. At the sub-national level, menstrual hygiene has been prioritized through free napkin initiatives of the governments of Tamil Nadu (Pudhu Yugam) Odisha (Khushi), Andhra Pradesh (Raksha), Chhattisgarh (Suchita), Maharashtra (Asmita), Kerala (She Pad).

Access alone is not enough

Research evidence, however, suggests that more needs to be done to “break the silence” and increase the level of awareness and dialogue around menstruation and eliminate inequities in menstrual hygiene access. This will require a multi-pronged approach involving capacity building, community dialogue and interpersonal communication among key stakeholders (including families, frontline community health workers, community influencers, NGOs) with the aim of improving menstrual hygiene knowledge, practices and health as well as shifting social norms and practices around menstruation. This will also entail targeted policy measures and resources to expand access to improved menstrual hygiene materials, particularly among disadvantaged populations.

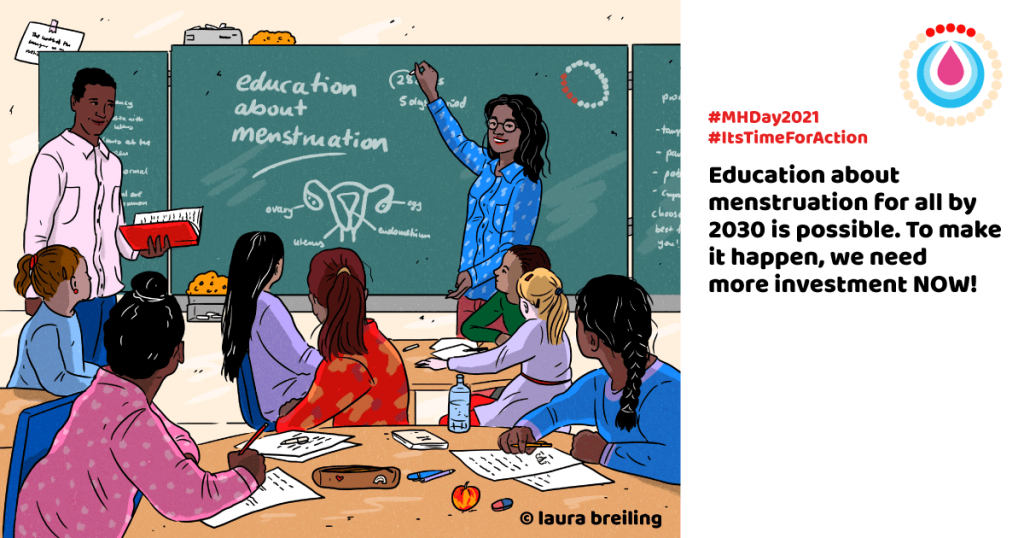

The 2021 Menstrual Hygiene Day calls for “Action and Investment in Menstrual Hygiene and Health”. Even as India continues its positive progress on access to water and sanitation, it is imperative that it upholds a policy environment that continues to mainstream gender considerations in sanitation and hygiene delivery.

Notes

- Satterthwaite, M., & et.al. (2013). Background Note on MDGs, Non-Discrimination and Indicators in water and sanitation. WHO/UNICEF Joint Monitoring Programme for Water Supply and Sanitation.

- Malhotra, A. (2013). Breaking the Silence: Open conversations around bodily changes and menstruation before its onset. UNICEF.

- George, R. (2013). Celebrating Womanhood. WSSCC.

- Malhotra, A., & et.al. (2016). Factors associated with knowledge, attitudes, and hygiene practices during menstruation among adolescent girls in Uttar Pradesh. Practical Action Publishing.

- Thakur, H., & et.al. (2014). Knowledge, practices, and restrictions related to menstruation among young women from low socioeconomic community in Mumbai, India. Front Public Health.

- Van Eijk, A. M., & et.al. (2015). Menstrual hygiene management among adolescent girls in India: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Publishing Group.

- Hennegan, J., & Montgomery, P. (2016). Do Menstrual Hygiene Management Interventions Improve Education and Psychosocial Outcomes for Women and Girls in Low and Middle-Income Countries? A Systematic Review. PLoS ONE 11(2): e0146985. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0146985.

- Kansal, S., & et.al. (2016). Menstrual hygiene practices in context of schooling: A community study among rural adolescent girls in Varanasi. Indian Journal of Community Medicine.

- Paria, B., & et.al. (2014). A Comparative Study on Menstrual Hygiene Among Urban and Rural Adolescent Girls of West Bengal. Journal of Family Medicine and Primary Care.

- Mohite, R., & et.al. (2016). Menstrual hygiene practices among slum adolescent girls. International Journal of Community Medicine and Public Health.

- Jogdand, K., & et.al. (2011). A community-based study on menstrual hygiene among adolescent girls. Indian Journal of Maternal and Child Health.

Featured Image: Flickr/ EpiscopalRelief

The author would like to thank Geetanjali GK for assisting with the analysis.

About the Author

Sujatha Srinivasan is a Senior Research Fellow at LEAD at Krea University, where she oversees the design and delivery of key strategic initiatives related to public infrastructure and basic services through a combination of research, outreach, and policy advocacy.