|

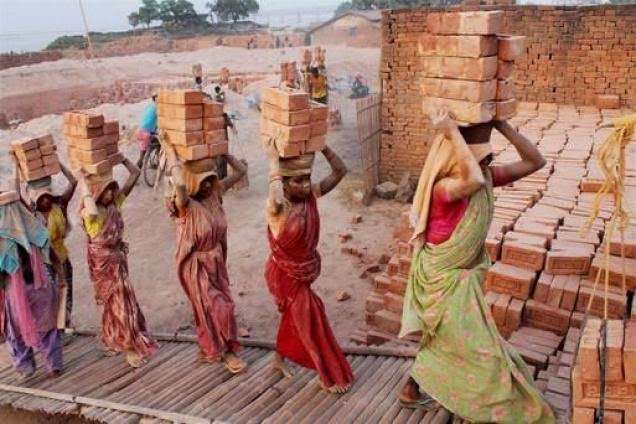

| Image Source: PTI |

Empowering the Poor or the Rural Elite?

By Deepti KC, Kalrav Acharya

In this general election, many candidates are banking on votes based on the performance of poverty reduction and social security schemes.

India has a plethora of such schemes, and the government has invested billions of rupees in them. In this context, especially with the anti-corruption debate making waves, we tried to study how these schemes are actually working.

India currently has the world’s largest poverty reduction initiative, the National Rural Livelihoods Mission (NRLM), based on the principle that communities (mainly women) be directly involved in the development process — taking control of resources and decision making.

Bureaucrats say it is a viable method of delivering development funds, thanks to its ability to circumvent a top-heavy, corrupt system.

At the same time, some experts argue that in heterogeneous communities with high social inequality and vulnerable groups could be excluded due to the possibility of the programme being captured by local elites. Our findings seem to support the latter view.

Under the purview of NRLM, the Tamil Nadu State Rural Livelihoods Mission (TNSRLM) recently stated that it aimed to cover 265 blocks by 2016. The mission is an expansion of the World Bank-assisted Pudhu Vaazhvu Project (TNPVP) that has already covered 120 blocks.

Livelihood issues

We conducted a case study in four villages where TNPVP was implemented four years ago. The selection of the sample was not representative of the whole population of 120 blocks; nevertheless, the challenges we recognised could work as lessons for all.

Central to TNPVP is a series of exercises on the Participatory Identification of the Poor (PIP), which aims to label every household in the village as ‘very poor’, ‘poor’, ‘average’, and ‘wealthy’ — relative to each other. We found that villagers present during these exercises ensured that their households were listed in the ‘poor’ or ‘very poor’ categories, also known as the ‘beneficiary list’.