Background

The COVID-19 pandemic rendered millions of workers unemployed in India; during the first wave, the estimated unemployment rate in India peaked at 24% in April 2020. The pandemic also brought to the forefront the vulnerability of the migrant population in India who bore the maximum brunt. The lockdowns during the pandemic not only constrained mobility, making it difficult for the migrants to return to their villages but also severely impacted food availability due to supply chain disruptions. Well-functioning welfare schemes are therefore important to cushion the impact of disruptions caused by pandemics or related situations. Responding to this, although central and state governments have announced various support schemes and accelerated implementation of existing schemes, research shows that there are issues pertaining to the infrastructure that facilitates smooth delivery of this scheme such as stock issues, and quality of digital infrastructure. The One Nation One Ration Card (ONORC) scheme was one such scheme whose implementation was accelerated during the pandemic owing to the distress caused to the migrant workers. This article explores issues with welfare delivery and ways to address them, specifically in the context of the ONORC scheme [1].

Under the traditional PDS system, the beneficiaries could obtain ration only through their designated ration shops. The ONORC scheme allows the portability of ration cards, thus enabling the beneficiaries and their families to claim ration from any fair price shop (FPS) (aka ration shops) across the country. Through this, the scheme mainly aims to smoothen the delivery of the ration to the beneficiaries across the nation. However, recent studies suggest that existing fault lines in the PDS, such as illegal diversion of foodgrains, beneficiaries not being able to procure ration from undesignated ration shops, hoarding, and delays in updating databases, have led to the exclusion of beneficiaries.

How does the ONORC scheme function?

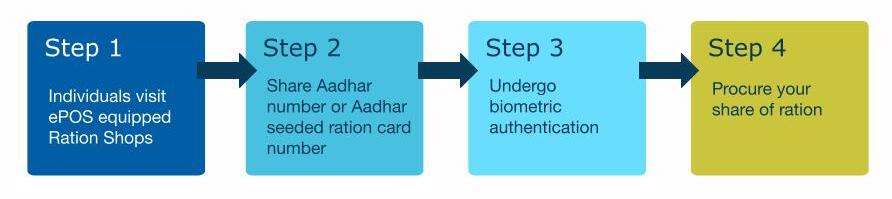

The ONORC scheme requires individuals to link their Aadhaar cards with ration cards to become eligible for the scheme. The linking of Aadhar cards stores pertinent details of individuals on the Integrated Management of the Public Distribution System (IM-PDS) portal. The scheme also requires every ration shop to install electronic Point of Scale (ePoS) machines in their shops, which retrieve information from IM-PDS and Annavitaran portals, where the identification details of each beneficiary are available [2]. Once any individual has seeded their Aadhar card with their ration card, they can procure ration by following a simple procedure shown in the figure below.

By simply scanning the thumbprint on the ePoS machine, the PDS shop owners can verify the credentials of beneficiaries, thereby allowing the latter to procure their share of the ration from any ration shop (i.e. PDS shop) in the states and union territories that have implemented ONORC.

The scheme was initially implemented in 12 states, in 2019 as a pilot. However, by 2021, due to the challenges emergency caused by the pandemic, particularly to the migrant workers, 32 states and Union Territories had implemented this scheme, with Chhattisgarh being the latest state to implement the scheme. While 69 crore beneficiaries under the National Food Security Act (NFSA), 2013 have been covered under the ONORC scheme by 2021, there are still more than 10 crore people who are excluded from the ambit of NFSA. Further, ground-level challenges such as lack of credible information across beneficiaries and FPS owners exist, which hinder last-mile delivery of this scheme.

Challenges with digital infrastructure

Given that the ONORC scheme primarily relies on the ePoS systems across all FPS shops, it is critical to ensure the availability and smooth functioning of ePoS machines. However, across the nation, only 47% (37,392 out of 79,050) of shops have adopted ePoS machines. As per the reply given by the Minister of State for Consumer Affairs, Food, and Public Distribution in the parliament, states such as Bihar and West Bengal, with some of the highest out-migration rates, have the least number of ePoS machines, 0.14% for Bihar and 1.27% for West Bengal respectively [3]. This is likely to make it difficult for families of migrants who stay back to procure their share of ration in these States, thereby. This could potentially worsen the issues of poverty and hunger in Bihar and West Bengal, where 50% and 21% of the population in states therewith are already multidimensionally poor [4].

The situation regarding the functioning of ePoS machines appears to be much worse, especially in the union territory of Delhi, which also experiences the second-highest influx of migrants after Maharashtra. As of July 2021, when Delhi implemented the ONORC scheme and installed ePoS machines across its 2554 FPS shops, there were significant delays in the testing of these machines, thereby causing delays in the rollout of the scheme (PTI, 2021). Even the shops with ePoS machines either do not have proper electricity or internet connectivity, particularly in rural areas where less than a third (29 %) has internet connectivity. As a result, shopkeepers are unable to check the eligibility of beneficiaries, thereby preventing beneficiaries from procuring ration. A case in point is Maharashtra where server issues continue to create issues for the smooth distribution of ration to eligible beneficiaries. Therefore, until India progresses in digital and technological infrastructure, the smooth delivery of ration or any other welfare scheme to people in need will continue to be a challenge. Naturally, failure to address these fundamental bottlenecks would also be tantamount to inefficient usage of resources.

A potential solution to these challenges is increased investments by the government as part of the Digital India initiative. First, leveraging its position as the founding member of the International Solar Alliance, the government could augment their investments in setting up solar parks near remote rural areas and transfer a proportion of its energy to these remote villages where unavailability of electricity prevents usage of ePoS machines. Secondly, the implementation and scale-up of broadband projects should be accelerated. While the Optical Fibre Internet Service marked a positive step towards increasing internet connectivity to the last mile in 2020, last-mile delivery of internet connectivity continues to remain a critical issue. In addition, providing subsidies for installing solar roofs could also potentially reduce the dearth of electricity supply. Furthermore, investments in setting up public WiFi spots in rural and urban areas that are closer to markets are most likely to have a positive impact on ensuring the smooth functioning of the ePoS machines.

Challenges with maintaining the database

Another aspect of the smooth functioning of the ePoS machine is the availability and quality of data along with proper seeding of Aadhaar cards with ration cards. Currently, the dearth of data on migration patterns across states, as highlighted in the Economic Survey 2016-17, limits the capacity of the state to produce credible forecasts of spikes in the demand for rations and manage the supply of rations accordingly. Ultimately, this creates stock issues across fair price shops, which again prevents beneficiaries from procuring ration despite being eligible for the scheme.

Policymakers will also need to minimise the exclusion of beneficiaries due to untimely updating of the databases that prevent ePoS machines to access and verify beneficiaries’ information on the centralised system, and ultimately the scheme to have its desired effect. Another reason for the exclusion of beneficiaries has been the deletion or invalidation of ration cards. In the process of linking the ration cards with Aadhaar cards to identify and weed out bogus ration cards, almost 3 crore ration cards have been deleted or cancelled by the states and union territories. While most of the ration cards were cancelled in the cases where bogus families and ineligible beneficiaries were found, there were also cases where ration cards were cancelled simply because the family, or the individual on whose name the ration card was registered, migrated from their native village. This increases the hardships of beneficiaries as they need to obtain a new ration card, which is time-consuming, especially for those who travel frequently for their work. With a poor rate of updating existing databases, these beneficiaries are deprived of ration for a longer period of time, thus ultimately contributing to an increase in their cost of living. The poor quality of digital infrastructure is a problem that not only affects the effective delivery of the ONORC scheme but several other welfare schemes as well. Direct Benefit Transfers schemes (DBT schemes) face similar challenges where either transfer are being made to the wrong accounts, or beneficiaries face network issues and biometric authentication issues during transactions.

Collection and availability of real-time data are critical for crisis prevention and impact analysis

Seeing as the role of biometric authentication technology is critical to the scheme, this points to the increased role of digital technology in planning policies and feeds into the broader vision of digital India – to transform India into a digitally empowered society. This increased role of technology could also facilitate the objective evaluation of welfare schemes such as that of ONORC as the increased role of technology in governance and delivery of welfare schemes could also be used to collect real-time data. For instance, timely collection of inter-state and intra-state transaction data could greatly help in studying the magnitude of the reach of the scheme. Furthermore, in addition to leveraging novel administrative datasets, a mixed-method approach, combining field surveys and qualitative interactions with FPS owners and beneficiaries, can be used to conduct a holistic context-specific assessment of ONORC and similar other schemes.

The subjects of economic and social planning, and maintaining supplies of essential services come under the concurrent list. Hence, like any other national-level scheme, the successful implementation of the scheme also depends on the ability of the centre and state to work in unison. Under the NFSA, the central government is responsible for the supply of food grains and the identification of beneficiaries, while the delivery of the food grains lies under the domain of state governments. For the sake of the smooth functioning of the scheme, it is important that the central government does not encroach on the autonomy of the state government. This means avoiding tensions between the state and the central government, which was evident in the reluctance of the Tamil Nadu government. Initially averse to implementing the ONORC scheme, the Tamil Nadu government argued that efforts to align several state policies on food are equivalent to encroachment on state governments’ autonomy.

A uniform level of supply of food grains to all states would be wasteful as every state differs in terms of size, population, the proportion of people living in poverty, number of migrants, and staple diet depending on the geographical settings. Thus, it is vital that the central government possess accurate data on these variables to anticipate the demand for food grains in states. The absence of timely data on migration patterns at the state level hampers the ability of the central government to supply the correct amount of food to states depending on their current and potential future needs. This was recently evident during food shortages during the COVID-19 pandemic whose maximum brunt was borne by migrant workers.

Conclusion

There are growing concerns over increasing inequality in India, which has exacerbated issues such as food insecurity and malnutrition. The ONORC scheme is an important step towards improving the portability of welfare benefits and addressing growing food security. However, structural inefficiencies like lack of digital infrastructure, issues with maintaining beneficiaries’ databases, and supply chain bottlenecks make it difficult for the food suppliers as well as food beneficiaries to benefit from such schemes. All these issues point toward the importance of effective investment and monitoring of the functioning of the FPS shops.

While ONORC has the potential to streamline the ration-delivery system and ensure fewer hurdles in meeting basic needs such as food, the entire value chain of making the system work needs to be backed by proper infrastructure. This requires greater monitoring to understand why ePoS systems have not been installed and how we can better maintain the database to avoid the exclusion of intra-state migrants. Regular audits of databases and digital, as well as policy literacy, could help to a greater extent in tackling these challenges. This will not only help in the effective implementation of such a policy but also help migrants deal with the issues of the non-availability of food.

Endnotes

[1] Kerala has announced a welfare package worth INR 20,000 crore consisting of cash transfers, free of cost food to poor families, and Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme (MGNREGS), and UP has pledged to provide cash handouts worth INR 350 crore.

[2] The Annavitaran portal hosts the data of distribution of food grains through e-PoS machines across states

[3] Out of the 1.23 crore migrant workers who returned to their villages in 2020, Bihar accounted for 12% of the workers and West Bengal accounted for 11% of these workers. Further, the intuition is that migrants travel alone, leaving their families behind. With low availability of ePoS machines, these members are not able to procure their share of ration under the ONORC scheme

[4] These figures are based on the multidimensional poverty Index of India, which is based on the methodology prescribed by the United Nations Development Programme and the Oxford Poverty and Human Development Initiative.

Cover Image: ILO

About the Authors

Sumiran Ardhapure is a Research Associate with the Financial Well-being and Social Protection vertical at LEAD. Sumiran holds a Master’s degree in Economics from the University of Warwick and a Bachelor’s degree in the same subject from Fergusson College, Pune.

Komal Jain holds a Master’s degree in Behavioural Economics from Gokhale Institute of Politics and Economics and did her B.A. (Honors) Economics from University of Delhi.