Behind these narratives, however, are other meta-narratives that cannot be captured in quantitative analysis. There’s been no rain, how can we practise agriculture? Why should we answer your questions, you’re not from the government. Why is this survey taking so long, I need to get going, it’s been two hours already! We don’t talk to anyone in the village. You’re walking around in heat just to talk to us? Let me offer you some lunch. Bewilderment. Resistance. Annoyance. Bemusement. Warmth.

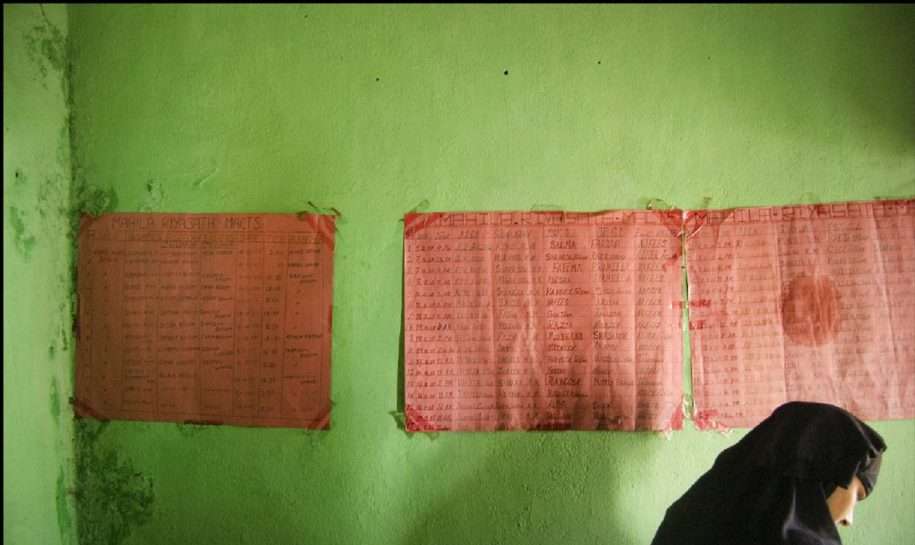

And behind these narratives, is yet another set of narratives that consumers of large-scale survey data are never exposed to, and perhaps rarely consider while working on analysis. Saar, how can you expect us to meet these targets – we need to walk eight kilometres with heavy medical equipment every day. Saar, there are rowdies in the village who have threatened to beat me if I show up here again. Saar, one request, please reimburse my motorbike petrol expenses, it’ll make work easier and faster. Why have you taken leave without any prior notice? What’s the completion status of last week’s allotments – I want an update immediately. No, I’ve already paid you half your salary, no more advances for you this month. Cyclones. Accidents. Thefts. Tears. Bus rides. Long walks. Longer interviews. Debriefs. And a lot of hard work.

As our survey data moves farther away from the rural households and organisational context within which they emanate to the analytical tables and reports where they are given meaning, a lot of this experience (perhaps rightfully) loses its relevance. However, this does not mean that these experiences are unimportant. And I’d like to take a moment here to acknowledge the effort and hard work of the field staff on not just KGFS-IE, but on all of CMF’s projects that helps a lot of insightful analytical work, and meaningful policy advocacy and engagement see the light of day. It’s easy to take all of this for granted. Thank you.

Shashank Kumar is a Research Associate on the KGFS-IE project in rural Tamil Nadu, where he has closely involved in coordinating the study’s data collection effort during the past few months.