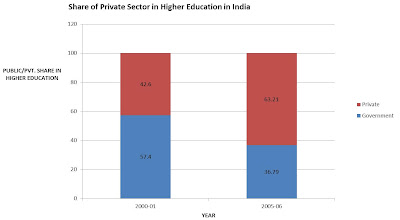

As a result, the GOI has spent a significant amount of time, money and effort in developing this sector in terms of good quality of education, teachers, institutions, and infrastructure. While elementary and secondary education in India is largely government-financed, the same is not true in higher education, as we see a large number of private stakeholders. Although, public private partnerships have the potential to bring efficiency and healthy competition, an increased private (for profit) sector presence in higher education could be problematic.

education. Given its status as a public good and as a core sector of the Indian economy, shifting the provision of education, and its associated costs to the private sector and onto individuals actually risks the under provision of education to those that need it the most.